Alien: Romulus: The Universe Doesn’t Care About You – and Neither Does Capitalism

The horror isn't the xenomorphs - it's that the characters are forced to confront them in order to survive under a ruthless economic system...

Well, it only took thirty-eight years, but we finally have a decent Alien sequel. Actually, more than decent: Alien: Romulus is damned good.

Now, it’s not flawless – far from it. Romulus is a bit too long, has nearly as many fake-out endings as Return of the King, and contains far too many forced references to earlier films.

But it’s a valiant effort nonetheless, not in the least because it manages to effectively return to the franchise’s anti-capitalist roots, while still retaining some of the prequel films’ existential themes as well as providing new twists.

Born in the USA

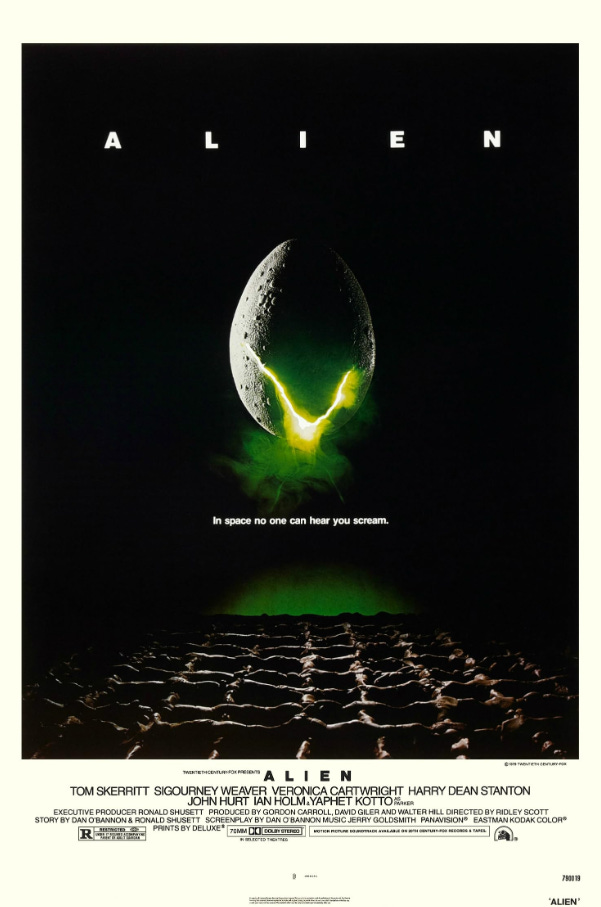

The first Alien is a brilliant, brooding horror film, a space movie made possible by the success of Star Wars, yet which jettisons George Lucas’s can-do optimism in favor of a ruthless nihilism. There is no benevolent cosmic “force” to aid the crew of the Nostromo; they’re completely on their own as they struggle against the untenable situation they’re forced into thanks to the greed of their unseen employers. The film’s eponymous creature (referred to in subsequent appearances as a “xenomorph”) is more than just a uniquely hideous creation – it’s a stand-in for capitalism (“unclouded by conscience, remorse, or delusions of morality”).

When the Nostromo’s surviving crewmembers learn that their science officer Ash is secretly an android who’s been ordered by the Weyland-Utani corporation to bring back the xenomorph even if it means killing them all in the process, they’re obviously outraged. Ash, on the other hand, is unphased. He is simply following his new corporate directive: “bring back life form – priority one. All other priorities rescinded.” “What about our lives, you son of a bitch?” a crewmember demands. Ash calmly reemphasizes, “I repeat: all other priorities rescinded.”

The values of the market triumph in this future, with the Weyland-Yutani corporation overtly and without remorse prioritizing the recovery of a potentially profit-generating creature over the safety and, ultimately, the lives of its employees.

The film barely takes pains to conceal its primary message that “profit motive above all” is the vilest way to organize a society. This not-so-subtle condemnation of the capitalist mentality was very 70’s – back then, the Civil Rights Movement, the Vietnam War, the Watergate scandal, the Church Committee revelations, and all the rest taught Americans that the realities of the system they lived under didn’t quite gel with the Leave it to Beaver America they’d been sold. The resulting social unrest was so unnerving to those who owned the commanding heights of the economy that they seriously worried – needlessly, as it turned out – that “the private enterprise system” would soon be overturned in some kind of revolution.

Accordingly, films of the era reflected an exceptional cynicism about American institutions – All the Presidents’ Men, Three Days of the Condor, The Parallax View; hell, even Steven Spielberg, not exactly known for political radicalism, made it clear that the villain of 1975’s Jaws was not so much the titular shark, but the small businesses which refused to put the safety of beachgoers over their bottom lines.

This is perhaps the most revealing indicator of cinema’s newfound cynicism toward American institutions. Even It’s a Wonderful Life (1946), considered so left-wing in its day that the FBI thought it was communist propaganda, insisted that it was just big business that was the problem. George Bailey was not fighting for the revolution; he was fighting for the triumph of main street over Wall Street. Jaws, on the other hand, suggests that there’s not much difference between the two.

Thus, Star Wars’ arrival two years later was significant not just for its special effects, but for inaugurating a major tonal shift back to a pre-Vietnam era where films were less critical of the status quo. The unprecedented success of Lucas’ “space opera” influenced an endless stream of mindless summer blockbusters, which for the most part had nothing to say1 about the politico-economic system – unless they were propping it up by reassuring audiences that everything is fine, no need for change.

Fortunately, Alien was released early enough (1979) that it was able to capitalize on the post-Star Wars obsession with outer space, yet still hang on to that 70’s cynicism – soon to be wiped out by the rah-rah jingoism of films like Top Gun, which sought to make American capitalism and imperialism cool again.

But Alien did more than despair about the exploitative behavior of employers: it also gestured, however faintly, toward a much more existential kind of horror. After all, a universe which produces such a monstrous form of life is clearly not being run on any kind of compassionate basis. It would take several decades for director Ridley Scott to return to that idea.

The first sequel, Aliens (1986), shifted from horror to the action genre – while still managing to be plenty horrifying. On top of crafting one of the best action movies ever, director James Cameron retained Alien’s anti-corporate themes, expressing them primarily via Paul Reiser’s company man Burke, one of the slimiest villains in cinematic history (Reiser’s sister hated the character so much that she punched him in the chest upon viewing the film).

Things quickly went downhill from there, however. While Alien 3 (1992) deserves credit for upping the ante in terms of sheer hopelessness (RIP Newt and Hicks), it simply isn’t a good movie. Even the special effects don’t help – they somehow look noticeably worse than either predecessor. Alien Resurrection (1997) was less gloomy, both aesthetically and metaphysically, but was nonetheless a far cry away from the first two films. This unnecessary sequel was essentially a Syfy Channel original movie with a big budget – albeit not big enough to make CGI xenomorphs look convincing.

Alien vs. Predator (2004), the first of two crossovers with the far less intellectually heady Predator films, was admittedly a great popcorn flick, but nothing more. Its sequel, Aliens vs. Predator: Requiem (2007), couldn’t even pull that off – it too was a popcorn film, but a very bad one.

Things changed when Ridley Scott returned to the franchise for the first time since the 1979 original to helm Prometheus (2012), a prequel that explored different themes by asking provocative questions about the origins and purpose of human life, the existence of God, the possibility of an afterlife, and the nature of the universe itself.

The results are admittedly uneven – Hollywood is not known for effectively tackling such themes – and as a result, the film has a mixed reputation. But it deserves praise for trying to do something new – combining H.P. Lovecraft with Chariots of the Gods. Indeed, the plot of Prometheus is essentially an homage to the latter, with the unsettling caveat that the former may have been right about the nature of humanity’s place in the cosmos. As the inimitable Barbara Ehrenreich put it in her analysis of the film’s themes, “Scott and his writers are confronting us with the possibility that there may be a God, and that He (or She or It or They) is not good.” [her emphasis]

Nightmares Both Economic and Existential

The characters in the original Alien films are all one variety or another of exploited workers. Whether they’re merchant mariners in space (Alien), enlisted Marine Corps grunts (Aliens), or victims of an intergalactic prison industrial complex (Alien 3), they have no time to ponder abstract philosophical questions, because they’re too busy merely trying to survive – first their jobs, then their encounters with the xenomorphs.

The protagonists of Prometheus, by contrast, are either trillionaire business executives or else scientists, engineers, full-time astronauts, and doctors – members of the Professional Managerial Class (or “PMC” - a term coined by Ehrenreich, incidentally), less burdened by the Darwinian struggle for survival under capitalism, and thus able to spend time on more esoteric matters like the origins of life and humanity’s purpose.

The main characters of Prometheus discover that human life originated with experiments conducted eons ago by “engineers”: humanoid aliens who seeded earth with their DNA for reasons unknown. In the film, dying Weyland Corporation CEO Peter Weyland travels to a far-off moon with a crew of scientists to meet humanity’s creators. He wants to know why they created us, what our purpose is, and if they can save us – well, him – from death. The only engineer they encounter responds to Weyland’s inquiry by killing him instantly, along with most of his crew, before blasting off for Earth in a ship loaded with cannisters full of a mysterious “black goo.” This noxious substance is a bio-weapon that can both manipulate the structure of DNA as well as kill indiscriminately.

The crewmembers who survive the engineer’s massacre are able to stop his ship from reaching its destination, thereby averting planetary genocide on Earth. But the situation is bleak otherwise. The Prometheus expedition was meant to answer questions like “who are we,” “where do we come from,” “what is our purpose,” and “what happens when we die.” In short order, they learn that the answers are “experiments,” “a petri dish,” “nothing,” and “nothing,” respectively. (As the mortally-wounded Weyland lies dying, he makes it known that he’s found the answer to the latter question: “there’s…nothing…”)

The engineers created humans, for reasons known only to them. Upon encountering their progeny, they quickly decide to wipe them out and start over, also for reasons known only to them. To the anguish of main character Dr. Elizabeth Shaw, they came to view their creations in much the same way you or I would view a wasp nest near our home – as something best eradicated.

Thus, Prometheus embraces a kind of cosmic horror that Alien only hinted at – the possibility that humanity is not the center of the universe, and that the universe, in turn, is not just indifferent, but actively opposed to human flourishing. The Alien prequel suggests that humanity’s conquest of the stars might not be such a wonderful thing, given that we’d be squaring off against a universe defined by an interplanetary Darwinism, teeming with far more advanced beings with the desire and means to exterminate all life on earth, and which is devoid of any ultimate meaning.

Losing Sight of the Big Picture

Prometheus ends with Shaw and android David jetting off to the engineers’ home world, in order to discover why they created humanity. This clearly indicated that a sequel would continue asking big questions. Yet by the time Scott got around to making Alien: Covenant, either he or 20th Century Fox or both decided to abandon that approach. With Shaw cruelly killed off before the film even begins (she’s been brutally murdered and experimented on by the insidious David), Covenant’s narrative abandons her quest for answers, and opts instead to explore less-grandiose matters, such as “what would happen if a emotionally insecure, metaphysically anguished android were given the time and means to experiment with WMDs?”

We learn that after David and Shaw reached the engineers’ home planet, David killed not only Shaw, but all of the engineers as well, by unleashing the black goo on them and their now-ruined city. Alone, David then commenced experimenting with the goo, using Shaw’s corpse as the requisite biological matter to explore its effects on organic tissue.

Having thus dispensed with the lingering questions Prometheus left unanswered, Covenant follows the crew of yet another spaceship, which crash lands on the engineers’ planet. There they encounter David and his hideous experiments, which turn out to have resulted in the creation of the xenomorphs. At this point Covenant becomes a paint-by-numbers Alien film – a xenomorph gets onto the ship, the crew has to kill it, and the survivors go back into stasis to head somewhere else. The twist this time is that David has snuck aboard, and intends to continue his vile experiments on the hapless survivors while they’re in cryosleep.

This impressively fiendish ending aside, Covenant errs in abandoning the compelling issues raised by its predecessor in favor of jerking the franchise back to where it started.

Synthesizing the Nightmares

Covenant’s flaws notwithstanding, both prequels cumulatively serve to inject existential dread into a franchise that had previously been concerned with the horror of economic exploitation. This finally brings us to Alien: Romulus, which for the most part returns to stress Alien’s idea that the politico-economic system humans have constructed – a capitalism that colonizes other worlds – mirrors and possibly even exceeds the ingrained brutality of the universe itself. In fact, Romulus stresses this point harder any of the earlier Alien films.

Romulus centers on a group of young, exploited workers (and one android) on the miserable mining colony “Jackson's Star” on planet LV-410. The protagonists are all trapped working for the Weyland-Utani corporation under an increasingly repressive contract labor scheme. They fantasize about a better life on the planet Yvaga, which requires a ten-year journey in cryosleep to reach. In the meantime, they’re stuck on LV-410, rife with industrial pollution, homelessness, rusty infrastructure, cramped living conditions, and their fellow immiserated workers. In other words, an American city, transplanted onto a world with beautiful Saturn-like rings – which no one can actually see, because the atmosphere is so congested with dirt and dust and various forms of industrial smog that it blocks out the sun.

Main character Rain Carradine is one such unfortunate worker, determined to avoid the fate of her parents, who suffered a similarly wretched existence before dying from the lung disease they picked up working in “the mines.” Rain finally reaches the required number of hours worked to receive a company-funded transfer to Yvaga, where she will actually be able to see the sun. But the corporation decides to up the required number of hours to qualify for such a transfer at the last minute, thereby consigning her to an additional five to six years of labor in the mines before being able to escape her hellish existence.

It’s all straight out of Capital Volume I, where Marx is increasingly outraged as he describes the Dickensian exploitation of English factory workers, especially children. For those who’ve never cracked open Marx’s behemoth work, Boots Riley’s radical black comedy film Sorry to Bother You may be a better comparison, given its darkly hilarious send-up of the heartless practices of monopolistic companies that prey on vulnerable workers.

Alien: Romulus is similar, but with no room for humor. This is a future where the likes of Jeff Bezos, Elon Musk, Richard Branson, and the rest of our modern-day space-obsessed Robber Barons have seeded the cosmos with their Ayn Randian, free-market values. Grassroots struggle for economic democracy has completely lost the fight against corporate exploitation in this grim future. While we do briefly see a few protesters and activists demonstrating against Weyland-Utani’s slave-like working conditions, the characters, extras, and even the cameras quickly pass them by. No one pays them any mind; they’re just some kooks best ignored – the ethos of the 2024 Democratic National Convention has prevailed in space.

Dejected, Rain meets up with a group of her friends, who plan to escape Jackson’s Star by flying the hauler Corbelan out of LV-410’s atmosphere in order to board a derelict, abandoned Weyland Yutani spacecraft that has mysteriously drifted into the planet’s orbit. They plan to steal the craft’s cryosleep pods, which will enable them to make the ten-year journey to Yvaga. While Rain is reluctant to take part in the scheme at first, she changes her mind while observing grimy, overworked company men heading off to the mines, which reinforces her determination to escape the fate of her parents.

Needless to say, things do not go well once the characters board the ship. It turns out to be the Renaissance, a major company research station. As shown in the opening scene, the Renaissance recovered the xenomorph among the debris of the Nostromo from the first Alien. Although Sigourney Weaver’s Ellen Ripley had blown the creature into the vacuum of space, we learn that it survived by constructing a sort of cocoon around itself. Once aboard the Renaissance, the creature was experimented on by Weyland-Yutani scientists (more on that later). But ultimately the creature could not be contained – what a surprise! It killed the station’s crew, and now the whole place is crawling with xenomorphs. Our main characters discover this the hard way shortly after boarding, and spend the rest of the film trying to escape the creatures before the creepy, Event Horizon-looking Renaissance crashes into LV-410’s rings.

The film puts its hapless characters through one disturbing sequence after another from here until the credits. To take just one example: we learn early on that Rain’s friend Kay is pregnant – never a good sign in these films, which “have always centered on the horrifying implications of sex, birth, motherhood, evolutionary development, and nightmarish corporate interference in all of those areas creating ever worse biological nightmares,” as Eileen Jones nicely put it in her review. Unaware of what awaits her on the station, Kay wistfully describes how glad she is that her baby will get to grow up on a world where people can actually see the sun. “Ooooof,” I and the people sitting next to me in the theater half-laughed, half-groaned. We know the film is going to be exceedingly cruel to this poor girl – and oh boy, it is.

Kay’s plight culminates in something truly horrific, evoking both the infamous squid abortion sequence from Prometheus as well as some of Alien: Resurrection’s few worthwhile ideas. What’s most interesting about this aspect of the film (I’ll skip the details for those who haven’t seen it) is that it takes the anti-capitalist themes of the franchise and merges them with the more existential ones imported from Prometheus. This is accomplished via the return of the black goo, which has been extracted from the xenomorphs by the Renaissance’s scientists, who managed to synthesize it for human consumption.

The Weyland-Yutani corporation’s plan is to use the goo (referred to by one character in an awesome callback as “the Prometheus fire Mr. Weyland died trying to find”) to mutate humans and make them more resilient to space travel, and therefore better suited for colonizing other worlds. So not only have the depredations of the company forced the protagonists to steal from the space station in order to escape their exploitation, but it has now decided that since its employees can’t withstand the harsh conditions that come with making new worlds fit for corporate profits, the solution is to mutate their DNA! Weyland-Yutani has thus gone from “building better worlds” to “building better people.”

There are some really interesting ideas to chew on in all this if you’re the kind of philosophically-inclined person who thinks about these films long after the credits roll. Granted, Alien: Romulus is primarily intended to be a frightening sci-fi horror flick. Its main aim is to entertain and terrify. It certainly succeeds – the film looks amazing, and despite a plethora of plot scenarios that fans of the franchise will be more than familiar with by this point, there are enough new twists on just how terrible being trapped on a ship full of xenomorphs would be that it doesn’t feel stale (I can’t believe no one has ever thought to do acid blood in zero-gravity before!).

But the philosophical questions raised by this film, via a successful amalgamation of the themes of prior entries, are profound – and disturbing.

Unsettling Implications

The way I see it, there are two unsettling implications suggested by these films. First, that a futuristic capitalism in space would be a nightmare. Second, that even if, in the future, capitalism were overcome, and humanity took to the stars under a more equitable system, what we might find out there may turn out to be just as cruel, if not more so.

In the real world, we’re so far away from solving capitalism’s myriad crises – climate change, endless wars, rapidly escalating income inequality and its attendant poverty, an eviscerated education system, rotting infrastructure – that it’s difficult to conceive of what things might look like after we’ve won. Indeed, even the mere possibility of winning often seems difficult to imagine.

But there’ve always been some that’ve speculated on what humanity might occupy itself with once it manages to overcome the chains of economic exploitation. George Orwell, a democratic socialist, wondered about this in some of his writing:

Most Socialists are content to point out that once Socialism has been established we shall be happier in a material sense, and to assume that all problems lapse when one’s belly is full. But the truth is the opposite: when one’s belly is empty, one’s only problem is an empty belly. It is when we have got away from drudgery and exploitation that we shall really start wondering about man’s destiny and the reason for his existence.

To some, such concerns might seem a bit premature - after all, perhaps we’d be better off ending economic exploitation first, then moving on to daydreaming about cosmic exploration. That debate aside, the science fiction genre has often served as a vehicle for such dreamers to imagine possible futures, both those beyond capitalism, as well as those beyond the stars. Sometimes, the two have been combined.

The most famous example of this is perhaps Star Trek, which took up Orwell’s questions about “man’s destiny,” and came up with answers that were basically optimistic. In the world of Trek, the struggle for socialism has already been achieved, and the results are generally excellent. “You see, money doesn’t exist in the 24th century,” a time-travelling Jean Luc Picard tells an incredulous 21st century woman in Star Trek: First Contact. “The acquisition of wealth is no longer the driving force in our lives. We work to better ourselves and the rest of humanity.”

In other words, the thing that the Bolsheviks thought would happen after they seized power – use of money simply fading away – has actually happened in this world. In the aftermath, humanity has taken to the stars to “seek out new life and new civilizations,” seemingly just for the hell of it.

And what’s more, the universe and its inhabitants are eager to receive the crew of the Enterprise. Sure, there’s still conflict now and again, but for the most part, the alien species that make up the United Federation of Planets are benign. In fact, they’re barely “aliens” at all – they look, think, and speak almost exactly as humans do.

So, capitalism has been overcome, and humans, needing something to do, ventured out into the universe and discovered…pointy-eared versions of themselves. Granted, this was partly due to budget constraints, especially in the 60’s. But it was also a failure of imagination. The odds that intelligent beings elsewhere in the universe would resemble humans – let alone possess a head with eyes, ears, and a nose; a body with two arms, two legs, fingers, toes, etc. – are basically zero.

Extraterrestrial intelligent life, having evolved under different circumstances, would more likely be entirely dissimilar to us – and thus difficult if not impossible to comprehend. Denis Villeneuve’s beautiful film Arrival, wherein two linguists struggle to devise a method of communicating with friendly but incomprehensible plant-like extraterrestrials, explores this idea guided by a spirit of awe. Indeed, one can imagine the vast difference between ourselves and potential alien beings as something quite wondrous.

Consider the octopus. Philosopher of science Peter Godfrey-Smith argues in Other Minds: The Octopus, the Sea, and the Deep Origins of Consciousness that, since they developed advanced brains and central nervous systems via a completely independent evolutionary pathway from humans, octopuses are the closest thing on Earth to intelligent aliens. It’s awe-inspiring to think that we have the rough equivalent of an intelligent extraterrestrial species right here at home. It’s also somewhat relieving, because octopuses and their fellow cephalopods are beautiful animals, and tend to be quite friendly. With the exception of the occasional Humboldt Squid or Blue-Ringed Octopus, they are perfectly safe for us to interact with, much as we may find them inscrutable.

But others have taken the idea of unfathomably different aliens in far darker directions. H.P. Lovecraft prophesied a hostile universe full of “eldritch things” that were not merely different from us, but terrifyingly so. Lovecraft’s alien races are not just strange, but so utterly antithetical to what humans are used to, that merely gazing upon them is often enough to send his protagonists over the edge. The ruling powers of the universe in Lovecraft’s mythos are far older than humanity, and they aren’t terribly interested in its well-being, either, focused as they are on their own nefarious designs. Much of his fiction concerns characters being driven mad after discovering that the universe is hostile to humanity, whose existence is revealed to be little more than a meaningless accident, and whose future is implied to be doomed.

This is the territory the Alien franchise explores. While the first film ponders the nightmare of being forced to work for a corporation that will sacrifice you in the blink of an eye if it means an increase in shareholder value, Prometheus suggests that capitalism, socialism, and the puny humans that struggle to bring about one or the other are all utterly inconsequential in the grand scheme of the cosmos. Alien: Romulus mostly focuses on the former theme, while still hinting at the latter - indeed, one character in the film screams it as he’s incinerated. After all, this film is a product of its own particular time and place, just as the original Alien was influenced by the political climate of its time, as discussed above.

Romulus was scripted in an era full of increasing anxiety as to whether or not progress is even possible, given the immense forces working against efforts to collectively improve conditions for most people. Inequality shows no signs of abating (despite a long-overdue push to revitalize the labor movement), and climate breakdown continues to accelerate by the day (I haven’t seen a positive development on that front in a long time). Accordingly, the main characters in Romulus are reminiscent of the kind of people you’d meet at a Bernie Sanders rally from 2016 or 2020 - young, exploited at work, and nervous about their future prospects - but with just enough daring and optimism that they believe they at least have a chance of extricating themselves from their circumstances. In real life, the Sanders campaigns failed (some might say they were sabotaged), just as the character’s plan ends in total disaster.

Still, in both the film and real life, not all is lost - although most is. The (few) survivors at the end of Romulus do indeed manage to head for Yvaga - although it’s very ambiguous what they will find when they get there, or if they’ll even make it at all. That ambiguity is how many people feel right now: there are causes worth fighting for, with at least the possibility of positive outcomes, although we won’t know for sure until we reach our destination, at which point it may well be too late if things don’t work out.

When contemplating such gloomy stuff, I’m often comforted by recalling something Ursula K. LE Guin once said. As she received a Medal from the National Book Foundation, the brilliant science fiction writer and anarchist declared: “We live in capitalism. Its power seems inescapable. But then, so did the divine right of kings. Any human power can be resisted and changed by human beings. Resistance and change often begin in art. Very often in our art, the art of words.”

Art like Le Guin’s novels has contributed a great deal toward that end. Art like the Alien films, on the other hand, contributes to pessimism. It suggests that in the future, capitalism’s power has proven to be “inescapable” indeed. And while Romulus’s final scene is at least somewhat optimistic, most characters in this franchise who’ve ended up in cryo-pods enroute to the next installment have come to bad ends.

What I take away from Romulus, then, is what I have always taken away from these things - that victory is ultimately unlikely. Furthermore, in the event that the construction of a more equitable economic system is possible, thereby allowing humanity to collectively pursue answers about its place in the universe as Orwell suggested, we may find out that, contra-Star Trek, the universe is as innately cruel as the capitalism that has just been overcome.

Now that’s horror.

This is not to say that Star Wars itself didn’t have anything to say – it’s long been rumored that Lucas intended the Rebel Alliance to be a stand in for the Viet Cong, with the Empire symbolizing the American military.