The Myth of Christian Abolitionism

Challenging lazy, unsustainable beliefs about the relationship between Christianity and slavery…

Review of An Emancipation of the Mind: Radical Philosophy, the War over Slavery, and the Refounding of America by Matthew Stewart

In case anyone was wondering, good old Texas is at it again. Last week, the New York Times reported that “Texas education officials are expected to vote this week on whether to approve a new elementary-school curriculum that infuses teachings on the Bible into reading and language arts lessons.” For obvious reasons, this provoked controversy, with many observing that the new curriculum would clearly violate the separation of Church and state, as it crosses the line from teaching about religion into straight-up evangelizing.

In turn, conservative state leaders trotted out the standard defenses, arguing that they would never – never! – use the public school system as a vehicle to proselytize. This being Texas, outside observers can be forgiven for being skeptical.

One of the most interesting things about the proposed curriculum noted in the Times report comes at the very end of the piece:

In a fifth-grade unit on racial justice, students would be taught that Abraham Lincoln and abolitionists relied in part “on a deep Christian faith” to “guide their certainty of the injustice of slavery.” But they would not be taught that other Christians leaned on the same religion to defend slavery and segregation.

It was one example, [theologian David R.] Brockman said, of what he called a “whitewashing of the negative details of Christian history” that “helps to promote Christianity as an inherently ‘good' religion.”

Three things about this.

First, Brockman and the Times are correct to point out the troubling omission of Christians who supported slavery. That would certainly be “whitewashing” American Christianity as an “inherently good” religion, as they say. But in fact, they do not go nearly far enough. Because the truth is, it wasn’t just that there were some “other” Christians who supported slavery. Rather, it was the overwhelming majority of not just individual Christians, but also Christian Churches and institutions, in the North and the South, that supported slavery.

Second – and this part is often obscured – from a Biblical perspective, they were entirely justified in doing so. Contrary to numerous deliberate evasions by its defenders, the Bible is an extraordinarily pro-slavery book – both Testaments. While conventional wisdom has it that pro-slavery clergy were “twisting” the message of scripture in order to justify slavery, the fact is that no twisting was necessary – ministers could simply cite the good book chapter and verse.

Third, Brock and the Times also overlook that it is misleading to say that Lincoln and the abolitionists relied “on a deep Christian faith” to bring an end to enslavement. As is often the case with history, the real story is much more complicated.

It’s long past time that we euthanize these myths. They continue to have deleterious effects on the discourse. Contemporary Christians – especially but not exclusively white conservative ones – continue to insist that their religion deserves credit for emancipation, when precisely the opposite is true. Fortuitously, the philosopher and historian Matthew Stewart has put out a gripping new book, An Emancipation of the Mind: Radical Philosophy, the War over Slavery, and the Refounding of America, which provides just such a euthanization.

Christianity, the Bible, and Slavery – Correcting the Record

Today, Stewart writes, Americans “take for granted that the motivations of those who opposed slavery were religious while the religion of those who supported slavery was merely an insincere and hypocritical cover for material interests.” But this stance, generally adopted without much critical reflection, is a gross distortion of the truth. In reality, the “dominant variety of American religion, in both North and South, was a cornerstone of the slave system, as essential to its workings as the racism with which it colluded.”

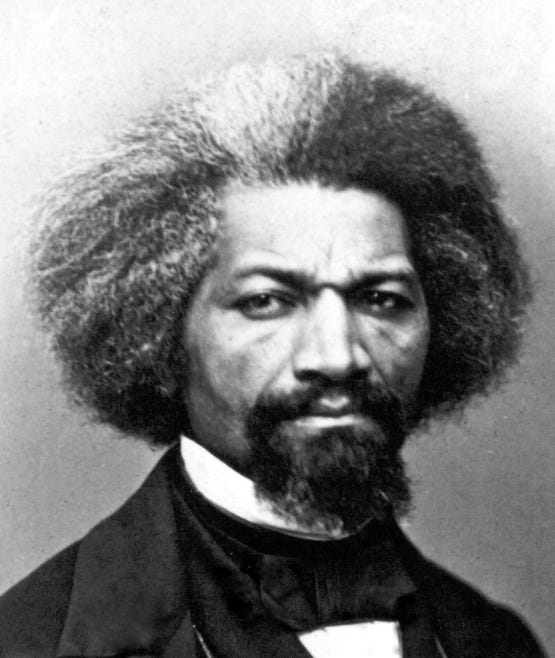

While many modern commentators overlook or obscure this, Stewart shows that leading abolitionists made this point explicitly and repeatedly. Frederick Douglass bluntly asserted that “[t]he church is beyond all question the chief refuge of slavery. It has made itself the bulwark of American slavery, and the shield of American slaveholders.” He claimed that Christianity was slavery’s “darkest aspect” and “the most difficult to attack.” Theodore Parker, whose commitment to abolitionism increased as his adherence to conventional religious doctrines did the opposite, declared of religious support for slavery that “[t]here are no chains like those wrought in the name of God and welded upon their victims by the teachers of religion.”

There were, of course, abolitionists who were devout Christians, just as the proposed Texas curriculum says. They initiated “early gestures toward abolitionism [which] were surely sincere and religiously motivated,” says Stewart. However, “they were [not] representative of general religious opinion.” Christians who opposed slavery were a tiny, tiny minority among the millions of faithful. The latter either supported slavery outright and despised abolitionism, or at the very least saw abolitionism as far more problematic than enslavement.

Furthermore, this small number of Christian abolitionists had a very hard time gaining any traction, for two significant reasons.

First, many religious abolitionists were more concerned with slavery’s effects on themselves rather than on the enslaved. “White evangelical abolitionism…was more concerned about the redemption of white souls than the emancipation of Black bodies,” Stewart clarifies. “[M]any evangelicals thought slavery was a sin for the same reason that beating your dog is a sin: because it reflects badly on the master, not because the slave is an equal.” Abolitionists uninterested in bolstering the reputation of the church did not hesitate to point this out, with Douglass offering a “damning assessment” of what he termed “the Church Anti-Slavery Society,” which he sneered “has little more than a paper life.” “It is for the salvation of the church,” Douglass lamented, “more than for the destruction of slavery.”

Commitment to belief in a supernatural realm often meant that the more secular project of terminating slavery was only a secondary concern – if even that. For example, the celebrated white abolitionist Quakers Theodore Dwight Weld, his wife Sarah Grimke, and her sister Angelina Grimke, eventually “retreated from antislavery activism” in order to focus on such higher callings as “apocalyptic cults,” “spirit manifestations,” and “idiosyncratic, New Age-style mind-body healing projects.”1

The second reason religious abolitionists did not get very far was because Christianity was not actually an anti-slavery religion – which, if you think about it, is a fairly major hiccup. “The scriptures were assembled in a time when slavery, like winter, was universally regarded as a fact of life,” Stewart explains. Accordingly, “the Bible…no more condemns slavery as such than it does the changing of the seasons.” Simply put, arguing that the Bible is against slavery would be like arguing that Mein Kampf is against antisemitism.

As if in anticipation that theologically-inclined readers might protest, Stewart runs through every relevant Biblical passage, and shows that not a single one condemns the concept of enslaving human beings. Really, this shouldn’t come as a surprise to anyone familiar with scripture, but it will surely startle those who lazily assume (as many modern persons do) that religious texts are among the most moral documents ever produced.

Stewart first surveys the Hebrew Bible, or the Old Testament, which

advises that a master “who beats their male or female slave with a rod must be punished if the slave dies as a direct result; but they are not to be punished if the slave recovers after a day or two, since the slave is their property.” It also insists you must give your slaves time off on the Sabbath, along with your donkeys. And that among the properties of your neighbor that you should not covet, aside from his wife and donkeys, are his slaves. And that selling your daughter into slavery is permissible, but you must be prepared to take her back “if she does not please her master.” It further recommends that you may keep slaves for life and bequeath them to your children, but that you should really make an effort to take slaves mostly (though not exclusively) from foreign tribes.

Abolitionists who were Christians attempted to counter this extremely inconvenient textual record by highlighting the tale of the Exodus from Egypt. “The glorious story of the Israelites’ escape to freedom across the parting seas was like gold to the anti-slavery camp,” Stewart writes. However, “the chosen people, upon getting clear of Egypt, promptly enslaved the Canaanites,” thus showing that “ending slavery per se was hardly part of God’s plan. Pharoah’s mistake was not to have practiced slavery, but to have enslaved the wrong people.”

Another “line of attack, advanced by evangelical abolitionists” in an attempt to skirt the Old Testament’s uncomfortably pro-slavery ethos was “to argue that ‘slave’ in the Bible (ebed in Hebrew) doesn’t mean ‘slave.’” Indeed, contemporary Christian apologists continue to invoke this silly idea, which was and is a transparent effort to avoid facing the obvious: that “notwithstanding subtle evolutions in practices over the time frame recorded in the Bible, ‘slave’ basically means slave.”

Abolitionists searched in vain for contradictory passages, but the Old Testament simply did not condemn slavery. It did, however, explicitly condemn a number of other practices. “Kidnapping, murder, bearing false witness, adultery, certain kinds of substance abuse, sodomy, wearing inappropriate garments under certain conditions – all are explicitly proscribed in the Bible, and the corresponding punishments are typically spelled out in excruciating detail. If slavery is the gravest sin imaginable, then wouldn’t you think that the Bible would just say so?” Stewart asks.

Proslavery Christians – who, again, were the vast majority – certainly argued along these lines. “Polygamy and divorce are at once and forever condemned, but not a syllable is breathed against slavery,” a proslavery minister remarked in a debate on the subject. Stewart emphasizes that this line of (theologically sound) reasoning was not merely a Southern phenomenon, either. “It would be a serious mistake to suppose, as many modern readers do, that proslavery Christian nationalism originated in the South or was confined there. Proslavery theologians had to change hardly a single word of the…theology they had imbibed from their teachers in the North.” Indeed, seeing as “Three out of every five clerics who published proslavery material were trained at Harvard, Yale, Princeton, Andover, and other divinity schools north of the Mason-Dixon line,” the simple truth was that “the leaders of the established churches of the North lined up overwhelmingly on the side of slavery in the battle of the Bible.”

Such views were common amongst non-Christian religious scholars as well. Rabbi “M. J. Raphall of Brooklyn,” for instance, thought it so obvious “that the Bible permits slavery that he declared himself mystified ‘how this question can at all arise in the mind of a man that has received a religious education.’”

Faced with an implacably pro-slavery Old Testament, religious abolitionists turned to the New Testament – ostensibly the happier half of the Christian Bible.

Yet “the Christian gospel, too, emerged from a slave society and coexisted with slavery for 1,800 years before the antislavery writers allegedly uncovered its true meaning.” Thus, it too “features masters and slaves,” and is in some ways worse than the Old Testament, since “the (partial) taboo on enslaving fellow religionists appears to have been lifted. There are Christian masters, in good standing with the church, and they own Christian slaves, in equally good standing.”

Stewart’s examination of the relevant passages shows how the New Testament provided absolutely no ammunition to the abolitionist cause - if anything, it contradicted it. “The clearest message on the subject in the New Testament is that slavery per se is fundamentally irrelevant to salvation. ‘Were you a slave when called?’ Paul asks the Corinthians. ‘Then do not be concerned about it.’”

This seeming indifference to slavery at times veers toward encouragement of it, as Stewart explains:

Inequality in this world is not only compatible with equality in a future world…but may indeed be a useful part of the preparation for it. Should you happen to find yourself enslaved in this world, Paul therefore emphasizes, the thing to do is to be as good a slave as possible. The relevant passages, recited millions of times in the American South across the pews and over the rows of cotton bushes, are as pellucid as anything in scripture ever is:

Slaves, obey your earthly masters with respect and fear, and with sincerity of heart, just as you would obey Christ. Obey them not only to win their favor when their eye is on you, but as slaves of Christ, doing the will of God from your heart. [Ephesians 6:5-6]

Slaves, obey your earthly masters in everything; and do it, not only when their eye is on you and to curry their favor, but with sincerity of heart and reverence for the Lord. [Colossians 3:22]

Unfortunately for the abolitionists, the New Testament, just like the Old, was hardly a clarion call to emancipation.

Searching for a Solution

All of this poses a major problem for contemporary religious people who like to think that their holy book (and, it is implied, their spiritual ancestors) inspired one of the most righteous causes in history.

The scriptures and the antislavery cause were wildly discordant, and most religious people were either militantly pro-slavery, or at the very least deeply wary of abolitionism. The miniscule percentage who were the exception had to find some way to reconcile their faith with their consciences. “Faced with the pile of textual evidence on the Bible’s malign indifference to slavery, antislavery advocates” of a religious inclination decided on “alternative interpretive strategies that would subordinate the letter of the text to the spirit – a spirit that, they did not doubt for a moment, favored justice for the enslaved.”

Such people “fled in droves to figurative methodologies of interpretation, where they have since been joined by the vast majority of those who identify with biblical religions.” But that required engaging in Olympian feats of mental gymnastics. An insistence that the Bible could not be read literally, and instead had to be interpreted, required people to (at least in this instance) “interpret” it in such a way so that it “meant” precisely the opposite of what it very clearly said – and on the most significant moral question humanity has ever faced, no less.

This leads to a fairly obvious dilemma that Stewart briefly raises. Since “interpreting” the Bible forces readers “to claim access to a standard of judgment to which the Bible and its prophets do not have access,” a standard wherein certain “principles come first, and the word of God matters only insofar as it confirms what [is] better deduce[d] from reason…why care at all about what the Bible has to say?” [emphasis added]

It’s not my intention to attempt an answer to that question here (as a devout atheist, it’s not really my problem). Those abolitionists who carried on with their work despite theological obstacles answered it either by (1) soldiering on with the Herculean task of interpreting scripture so that it meant the reverse of what it said, or else (2) by ditching religion entirely and embracing “infidel” status.

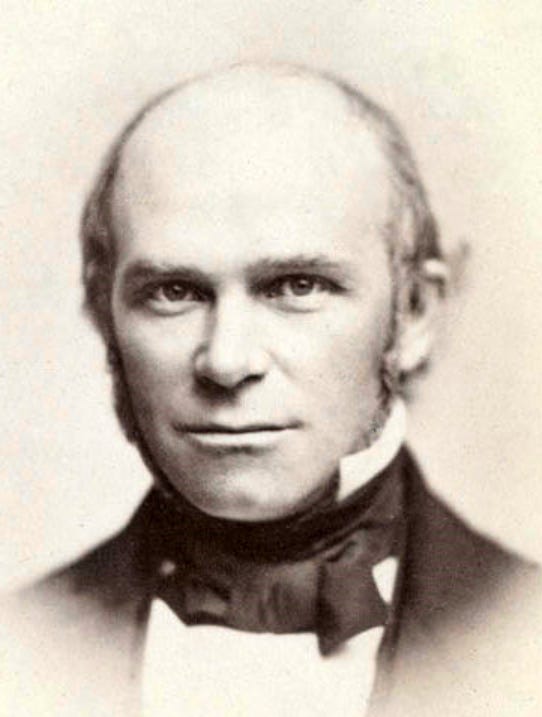

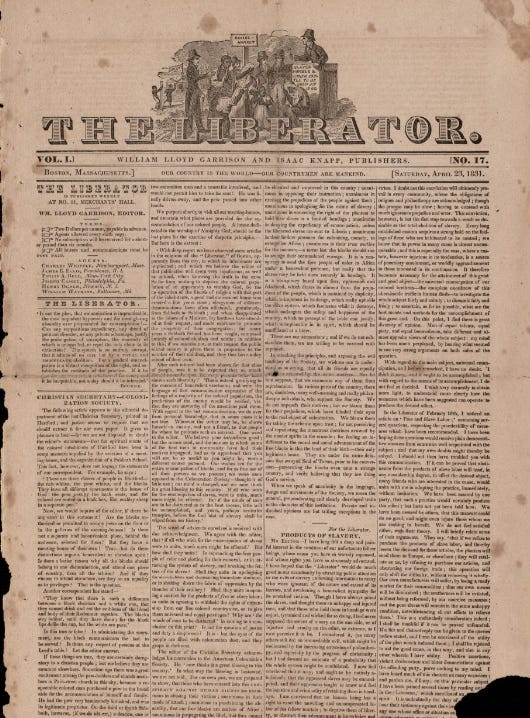

“In the early iterations of their counterattacks on the church of slavery triumphant, the abolitionists went out of their way to declare that their quarrel was with the churches, not with the religion of Jesus itself,” Stewart explains. But “as the battle wore on, it became clear enough that the battle was with the Bible, too.” Leading abolitionists began issuing proclamations like this one from William Lloyd Garrison’s abolitionist publication The Liberator in 1845: “To say that everything contained within the lids of the Bible is divinely inspired…is to give utterance to a bold fiction. To say that everything in the Bible is to be believed, simply because it is found in that volume, is equally absurd and pernicious.”

This abolitionist “attack” on “established theology” was taken up “with renewed vigor.” Another Liberator article from 1851 was headlined, “The Bible Not an Inspired Book.” “By 1858, Henry C. Wright felt free to dedicate a whole book to The Errors of the Bible. The Bible, viewed as a source of infallible truth, he concludes, ‘has ever been an enemy to human progress in knowledge and goodness.’” [emphasis added] Garrison himself ultimately came to the conclusion that “all reforms are anti-Bible.”

This led to a permanent rift between abolitionism’s “evangelical wing” and the rest of the movement. The latter’s attacks on religious institutions and texts was scandalous enough, but “The last straw was the growing association between abolitionism and the ungodly struggles for women’s rights and workers’ rights.” “[W]omen filled the rank and file of the antislavery societies,” and “the nation’s leading abolitionists – Douglass, Foster, Maria Stewart, Sojourner Truth, Lucretia Mott, and Lucy Stone among them – were its most outspoken feminists.”2

For the many of the pious, such causes were deeply troubling. “For those committed to supporting existing hierarchies of status and property, gender equality posed a threat at least as ominous as that of racial equality – a threat that could only be met with urgent appeals to the theology and science of gender difference.”

This marked a sharp break between the two “wings” of the struggle. “Once separated from the radical core of the movement, the evangelical contingent fell into some of its worst habits before dwindling to irrelevance.” This left those religious abolitionists who advocated nonliteral interpretations of scripture, along with those who gave up on religion altogether, to carry the struggle forward. The ideas which influenced them are another major theme running through An Emancipation of the Mind.

Germans Were Good, Once

Stewart’s doctoral work in philosophy at Oxford concerned radical German Enlightenment philosophy, which on the surface might not seem to hold much relevance to American debates over slavery. Yet by examining the written works of figures like Douglass, Parker, and even Abraham Lincoln, Stewart discovered that German radicals had a major influence over these figures and their cause. With religion worse than useless for the antislavery effort, the more effective abolitionists turned to radical philosophy for inspiration. In many ways this is the most interesting aspect of An Emancipation of the Mind, since the influence of Enlightenment thinkers, particularly of German radicals, is almost never mentioned in standard accounts of this period.

After the European revolutions of 1848 were largely repressed, many German immigrants fled to the United States, where they continued their activism in support of a more just and equitable world. These “48ers” were quick to impress the abolitionists, particularly Douglass:

Frederick Douglass…developed a fascination with German culture. He snapped up German grammar books and started to teach himself German. He put his daughter Annie, too, in German lessons. “To no class of our population are we more indebted for valuable qualities of head, heart, and hand, than the German,” he pronounced. His fondness for these immigrants of the mind had everything to do with where they stood on the only issue that mattered. “A German has only to be a German to be utterly opposed to slavery,” he said.

However, Douglass was also influenced by the 48ers on other issues. Partly through the influence of a woman named Ottilie Assing, a 48er who Douglass grew quite close to, he developed an interest in what is often termed “freethought,” which essentially means religious skepticism. Abraham Lincoln was also an avid consumer of this literature, which in turn drew influence from figures like Friederich Schleiermacher, Ludwig Feuerbach, and Karl Marx. (Many people probably don’t know that Lincoln and Marx briefly corresponded, and that the latter was keenly interested in the success of the Union cause during the Civil War, writing excessively in support of it.)

“Wasn’t much of this simply revolutionary atheism?” the New York Times asks in its review of Stewart’s book. “Yes, it was,” the reviewer answers, “and it’s a bit of a shock to find out how close Lincoln and Douglass were to these ideas, though they paid lip service to more conventional Christian beliefs when translating them for the public.” Indeed, much like how many of America’s founders were Deists, but often preferred to keep this private (a subject about which Stewart has also written), Lincoln appears to have been careful not to reveal too much of this radical influence in public utterances. But through an examination of his writings, as well those of people closest to him, Stewart demonstrates that Lincoln, too, was greatly influenced by German radicalism, which in turn led to him adopting Deist-like religious beliefs, in addition to influencing his perspective on abolition.

Implications

An Emancipation of the Mind is a fascinating, accessibly written book that dispels some annoyingly resilient myths as well as narrates some seriously interesting aspects of Civil War-era history that have been largely ignored up until now. Of course, it is not without its flaws, and they are at times quite serious. For one thing, like Stewart’s earlier book on the American founders and religion, there are more than a few traces of what I call “founding fathers worship.” People who write about the intellectual interests of figures like Jefferson, Washington, Adams, et. al. too often come to view these men as demi-Gods in a kind of secular religion of the American state, not the deeply flawed human beings they were. Stewart argues, for instance, that the system these men set up via the Constitution was basically liberatory, but that the American experiment was later hijacked by a counterrevolution led by slaveowners. This obviously won’t do – many of these men (Jefferson, Washington) were slaveowners themselves, and the American Revolution they led plus the Constitution they wrote both went out of their way to protect the peculiar institution. Slavery is a foundational element of the United States, not a “counterrevolution” that occurred afterwards. I think the historian Gerald Horne was well within his rights to compare this misty-eyed attachment to the cult of the American founders to uncritical nostalgia toward Stalin in Russian culture.

My other major issue with the book is that there is no discussion of how Stewart’s ideas relate to existing explanations for why the Union government ultimately decided to pursue eradication of the slave system. As much as a secular leftist like me would love to believe that it was all because honest Abe read a bunch of German materialists, as Eric Williams famously showed in the British context, it’s generally far less honorable interests that tend to have the most influence over such issues. And indeed, Thomas Ferguson notes in his criminally under-appreciated study Golden Rule, which looks at the influence of capital over the American political system, that “leading figures in every sector of the Northern business community played some role in the abolitionist campaign of the 1850s, and indeed statistical studies have demonstrated that they were far overrepresented among that campaign’s leaders.” That doesn’t make Stewart wrong, but it does mean that there were many factors influencing the fortunes the abolitionist cause beyond the lofty ideals he is concerned with.

But on the whole, I’m tremendously grateful that Stewart has written this book. The myth that Christianity was somehow the impetus behind the abolition of slavery has long bothered me, not only because it is such a risible distortion of the historical record, as we’ve seen, but also because of how insidiously it is invoked in the present. For example, one of the contemporary Christian right’s more curious talking points is that they are the “new abolitionists.” They trot out this rhetorical flourish when discussing their opposition to abortion, which they view as a courageous stand against the evils of child-murdering leftists. As Christianity Today put it, “many pro-lifers…view abortion as parallel to slavery, in that it treats a particular kind of human being as less than human and undeserving of human rights.” Many of these pro-lifers claim to be “inspired by slavery abolitionists.” Thanks to Stewart’s book, we know that the ideological ancestors of these anti-abortion crusaders were those on the side of chains, not abolition.

But I also think that An Emancipation of the Mind has implications for the left as well. In contrast to their freethinking forebears, many contemporary leftists have gotten into the bad habit of insisting that progressive causes and religious ideologies actually go hand-in-hand. Certainly, there have been real examples of this – the Civil Rights Movement, Christian Socialism in the UK, liberation theology in Latin America, etc. But as the engrossing narrative of An Emancipation of the Mind forcibly reminds us, just as often, the opposite was true. If there’s ever going to be an honest dialogue about the proper role of religion and religious belief in American life, we have to be honest with ourselves. Books like this help us do that.

This is why, as I’ve argued in the past, it’s a bad idea to encourage religiosity or “new-age woo-woo” in progressive spaces – because contrary to what is often said, such beliefs are (a) false and (b) major distractions from political projects that actually matter.

For the classic survey of this intersection, see Angela Davis’s Women, Race and Class.