Trump and MAGA Are Not Against "the Establishment"

The "populist right" is a con game, not a viable alternative to mainstream politics...

The views expressed in this article are those of the author, expressed in an unofficial capacity, and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Navy, Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government.

There is a ubiquitous story about American politics in the Trump era, which argues that both the left and the right have become increasingly opposed to “the status quo.” There are a few versions of this idea floating around, but they all revolve around the same basic narrative, which goes something like this: the post-Cold War rise of neoliberalism and its resulting wealth inequality and societal dislocations have triggered hostile reactions on both sides of the political divide. On the left, the opposition to neoliberalism first crystallized in the form of the Occupy Wall Street Movement following the 2007-2008 Great Recession, and later in the Bernie Sanders presidential campaigns. On the right, this thinking goes, we saw parallel developments: first the Tea Party Movement, which erupted at the same time as Occupy, and later, of course, in the rise of Donald Trump and the political currents that carried him to victory. In short, there has been a rise of what is often referred to as “populism” on the left and the right.

A vivid example of this narrative is the premise behind the pairing of media commentators Krystal Ball and Saagar Enjeti. Initially hosts for The Hill TV’s online program “Rising,” and now hosts of their own show “Breaking Points,” the two pundits are said to be indicative of the “populist” trend. As the title of their book The Populist's Guide to 2020: A New Right and New Left are Rising indicates, the duo represents both perspectives. Ball is on the “populist left,” and Enjeti is on the “populist right.” Yet both disdain “mainstream” views, and often come together around seemingly shared interests like a commitment to working class politics and an opposition to “endless wars” overseas. As the blurbs on the back cover of the book indicate, Ball and Enjeti’s project appeals to a wide range of people – figures as diverse as Nina Turner, Andrew Yang, Tulsi Gabbard, Kyle Kulinski, and Tucker Carlson all provided glowing endorsements.

The “populist left and right” narrative, then, is an update of the infamous “horseshoe theory,” which posits that as the right and left get more extreme, they gravitate toward one another, like the ends of a horseshoe. Now, this idea is almost exclusively promoted by halfwits, whose engagement with political theory never made it past the “Wikipedia stage.” It is normally invoked to suggest that both political “extremes” are equally bad, and that the truth (and, by extension, good politics) lies somewhere in the middle. But the “populist left and populist right” argument flips the horseshoe theory on its head. It argues that it is actually the political center that is the problem, that the “populist” left and right are correct to oppose it, and that these two groups have quite a bit in common and should thus make common cause.

This narrative is at least partially correct. It is true that the American left was “revived” by events like the Recession, and that for the first time in a long time, Occupy Wall Street and the Bernie Sanders campaigns allowed for the (limited) return of a more radical kind of politics, one skeptical, if not outright opposed, to capitalism itself. The milquetoast liberalism of the post-Reagan, Clintonite Democratic Party was finally seen for the embrace of conservatism that it was, and all of a sudden it became cool to fight for socialism again. While no one on the left would argue that Sanders or the movements around him were flawless, their appearance on the political scene undeniably represented a rupture; one that the ruling class was rightfully fearful of. For the first time in decades, a viable political movement was coming together around class issues – taxing the rich, raising wages, ending America’s embarrassing and cruel private health insurance system, making public college tuition free, and offering at least some skepticism toward overseas military entanglements.

The “populism of the left and the right” narrative falters, however, when it suggests that there is a “new” political right-wing that is also skeptical of “the status quo” (or “elites,” or “the establishment,” or “the deep state”). While many ordinary people who consider themselves to be “on the right” politically might vaguely intuit that something is wrong with the way things are, the movements and their leaders that claim to speak for such people – first the Tea Party, and now Trumpism – have never had the slightest intention of making any concessions to the poor or the working class. Neither Steve Bannon nor Tucker Carlson nor Donald Trump will ever fight for a living wage, single-payer healthcare, paid maternity leave, or free public college. Their project was and is to divert anger at the politico-economic system toward outlets that don’t threaten concentrations of wealth – namely, the Republican Party.

The historian Quinn Slobodian has carefully explained why the Trumpian right – as well as the global “populist right” generally – is not really a rejection of neoliberalism, but rather a mutant strain of it. Challenging this idea that there is “a face-off between populism and neoliberal globalism” on the political right, Slobodian argues that “neoliberalism and nativism only appear contradictory,” and that “so-called populist parties” on the right “represent a strain of free market globalism, not its opposition.” Indicative of this “convergence” between “neoliberalism and social conservatism” is the Trumpian right’s hatred of immigration and immigrants.

Traditionally, neoliberalism has favored “the free movement of capital, goods, and (sometimes, but not always) people across borders.” However, as that qualification implies, there has always been a prominent strain of neoliberal thought skeptical about the latter. This more overtly racist and Western chauvinist breed of neoliberalism essentially argues that “some cultures — and even some races — might be predisposed to market success while others were not,” and that “cultural homogeneity was a precondition for social stability, the peaceful conduct of market exchange, and the enjoyment of private property[.]” “‘Knowledge, goods and ideas’ should be free to migrate,” one representative of this tradition has argued, but people “did not have to move ‘in large numbers.’ That had already ‘brought nothing but deterioration.’” Indeed, “‘it would be bad if mass migration threatened global free trade,’” this figure continued. “People must remain fixed so that capital and goods can be free.”

The implications of this for our understanding of the Trumpian right should be obvious – they hate immigration not just because they are racists, but because their racist beliefs lead them to believe that immigration threatens neoliberal capitalism more broadly. They are not so much trying to end neoliberal capitalism as they are trying to protect it from what they see as an inherently threatening horde of nonwhite migrants. (This may well explain Steve Bannon’s hatred for figures like Elon Musk and Vivek Ramaswamy.) Their misleading rhetoric notwithstanding, “the parties dubbed ‘right-wing populist’ from the United States to Britain and Austria have never acted as avenging angels sent to smite economic globalisation,” Slobodian maintains. “They have offered no plans to rein in finance, restore a golden age of job security, or end world trade.”

This certainly applied to the Tea Party movement, which – unlike the grassroots Occupy Wall Street – was an “astroturf” phenomenon funded and organized by the obscenely wealthy in order to trick reliably gullible conservative Americans into supporting policies that would hurt their interests by – what else – disguising them beneath social conservatism and racism. As the journalist Jane Mayer reported in her book Dark Money, “although many of its supporters were likely political neophytes, from the start the ostensibly anti-elitist rebellion was funded, stirred, and organized by experienced political elites.” “The Heritage Foundation, the Cato Institute, and Americans for Prosperity” – all far-right, pro-free market think tanks funded by the Koch Brothers among other billionaire families – “provided speakers, talking points, press releases, transportation, and other logistical support.” These figures attempted to mobilize white racism and put it in the service of their primary goals – destroying what was left of New Deal social democracy. David Koch himself publicly decried Obama (who in reality was a very neoliberal figure) as an “antibusiness, anti-free enterprise” president, on the grounds that he had an “African” outlook derived from his Black father. Whether or not this plan to utilize racism in favor of free-market aims actually worked is up for debate – as Mayer noted later in her book, surveys of everyday Tea Party members suggested that none of them were in favor of things like privatizing Social Security or Medicare - among the primary goals of the movements’ leaders and funders.

This may be why Trump took a different approach, campaigning on “saving” those programs and on opposition to “free trade” agreements like NAFTA and the TPP. Campaign rhetoric aside, however, the idea that Trump and his team were a group of pro working-class avengers out to do battle with “the establishment,” challenge “the deep state,” or “drain the swamp,” was always laughable. Trump’s most significant legislative accomplishment during his first term was a gigantic tax cut for the wealthiest sector of the population (a sector that, not coincidentally, happens to be the Republican Party’s primary constituency). Of course, Trump is a billionaire, so he shares an obvious class sympathy with his fellow one-percenters.

Furthermore, Trump may have railed against Goldman Sachs on the campaign trail as a convenient way to ding Hillary Clinton’s terrible record of fealty toward Wall Street, but this was just rhetoric. Once in office, Trump appointed a number of Goldman Sachs alums, and they formulated policy exactly as you’d have expected them to. Trump appointees Steve Bannon, Dina Powell, Steve Mnuchin, and Gary Cohn had each put in many years of service working for the vampire squid, and everyone with a brain cell understood what their presence in the Trump administration meant.

In addition to tax cuts for the rich, these people were responsible for such “anti-establishment” policies as gutting the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (established in the wake of the recession to provide at least some protection for ordinary people against predatory financial institutions) and the Estate Tax (aimed at preventing the rise of an oligarchy by mildly taxing extremes of inherited wealth). On the latter policy, Trump claimed to have had the interests of his beloved workers and farmers in mind (“To protect millions of small businesses and the American farmer, we are finally ending the crushing, the horrible, the unfair estate tax”). Of course, since the tax only applied to inheritances worth more than $5.5 million ($11 million for couples), this was an obvious lie. Treasury Secretary and Goldman alumni Steve Mnuchin was far more candid: “Obviously, the estate tax, I will concede, disproportionately helps rich people.”

The idea that Trumpism was/is a threat to “the establishment” is also highly suspect when you look at the area that I specialize in – foreign policy. Frustratingly, this is also a topic where otherwise sensible people become very, very confused. As with Trump’s pretending to care about workers, much of this confusion stems from people paying far too much attention to his rhetoric and not nearly enough attention to his actions.

When Trump campaigned in 2016, he made the unusual choice to harshly berate the previous Republican president, likely because he intuitively and correctly grasped that this would endear him to voters fed up with “the forever wars.” As I’ve written about before, Trump blasted the George W. Bush administration for lying about WMDs to justify the Iraq War, for allowing 9/11 to happen, and other things. Such criticisms were perfectly true, as were Trump’s criticisms of Clinton’s connections to investment banks. But just like those criticisms, Trump’s foreign policy critiques were largely a way to go after an opponent, namely Jeb Bush, rather than indicators of what his actual policies were to be like.1

And indeed, once in office, Trump escalated Obama’s drone wars, his support for Saudi Arabia (which at the time was carrying out a genocidal siege against Yemen), and his support for Israel. Trump also undid two of Obama’s only positive foreign policy accomplishments: the rapprochements with Cuba and Iran. Trump even attempted to start a war with the latter country, and attempted to overthrow the government of Venezuela. Furthermore – and this really needs to be emphasized, because even in 2025, goofy MSNBC-addicted liberals still refer to Trump as a “Russian asset” – Trump was, as NPR once put it, the “toughest ever” on Russia. Like me highlighting the importance of differentiating between rhetoric and reality, a member of the hawkish Atlantic Council think tank told NPR that “When you actually look at the substance of what [the Trump] administration has done, not the rhetoric but the substance, this administration has been much tougher on Russia than any in the post-Cold War era.”

This, of course, was a very, very bad thing, since Trump’s policies drastically increased the risk of nuclear conflict between the two countries which between the two of them held most of the world’s nuclear weapons. It also helped lay the groundwork for the present crisis in Ukraine. Indeed, less than a year into his first term, Trump went well beyond Obama’s nonlethal support for Ukraine by shipping them weapons, thereby escalating the conflict considerably.

You could also tell that Trump was not an opponent of the foreign policy establishment by looking at his appointments. Trump hired a rogue’s gallery of neoconservatives and other Reagan/Bush II-administration fanatics to his national security team. Prominent examples included Mike Pence, Mike Pompeo, Gina Haspel, Elliott Abrams, and of course, John Bolton. Many MAGA folks, and even (sadly) a few contrarians on the left, try to defend Trump on this, or at least try to rationalize his behavior. One argument they make is that Trump was somehow “forced” to work with these people against his will. Another was that no matter how they ended up in his administration, they were at-odds with Trump’s fundamentally anti-interventionist foreign policy instincts. Both of these ideas are false.

Regarding the idea that Trump was somehow “forced” to work with such “deep state” denizens: who was Trump forced to hire, and who forced him to hire them? Take John Bolton, unquestionably the worst of the bunch. An article for Compact describes Trump as “having been forced to compromise with old GOP hands by including the likes of the arch-hawk John Bolton in his Cabinet.” But Trump was not forced to work with John Bolton – he went out of his way to select John Bolton. Trump had told Chuck Todd as early as August 2015 that he “watches the shows” and considers Bolton a “tough cookie” who “knows what he’s talking about” and who was “terrific.” When Trump later soured on his first National Security Advisor H.R. McMaster (another national security state hack), he immediately replaced him with Bolton. No one forced Trump to do this; as the interview with Todd suggests, Trump had long been an enthusiastic admirer of Bolton’s, thanks to the latter’s many Fox News appearances.

To the second point about Trump’s instincts, while it is true that on some issues (namely, Afghanistan) Trump was indeed less interventionist than many of those around him, more often than not, the opposite was true. For example, according to Bob Woodward’s book Fear: Trump in the White House, Trump wanted to assassinate Syria’s Bashar al-Assad, as well as to pre-emptively attack North Korea. The “deep state” turned out to be less aggressive than Trump himself, seeing as how in both cases, they had to prevent Trump from carrying out such insane schemes (and even then, Trump still bombed Syria twice in two years). And as already mentioned above, on the whole, Trump’s foreign policy record was largely a more aggressive version of that of his predecessor.

Ok, so Trump enthusiastically embraced the “swamp creatures” he claimed to want to vanquish, and he was not an antiwar president. But there’s a third argument, which says that at least Trump also brought “populist right” figures into power, and that these people were genuinely opposed to warmongers like Bolton and “the establishment” they represented. In Trump’s first term, the standard exemplar of such “populist right” sentiment was Steve Bannon, considered to be Trumpism’s leading intellectual (to the extent that such a description isn’t an oxymoron).

But once again, we are confronted with the bloody obvious yet seldom-noticed fact that figures like Bannon are hardly opponents of “the establishment’s” foreign policy views, but rather peculiar variations of them. Before he got into politics, Bannon was a Naval Officer and then a Goldman Sachs banker – not exactly occupations known for producing political radicals. He then became a filmmaker, unleashing a torrent of frothing-at-the-mouth documentaries in an attempt to become a sort of far-right Michael Moore.

Tellingly, the Bannon-directed film “Occupy Unmasked” smeared Occupy Wall Street as a threat to the foundations of all that was good about America. As Michael Tracey put it in his review for the Nation, the film’s “central thesis holds that the movement was founded as – and remains – an elaborate front for the Obama re-election effort, having been surreptitiously organized by actors ranging from the SEIU, Rachel Maddow and ‘professional anarchists’ to Amy Goodman, Hamas, Russia Today, Matt Taibbi and the Anonymous hacktivist collective.” In interviews promoting the film, Bannon compared Occupy protesters to “Nazi brownshirts.” Funny how former Goldman Sachs employees always seem to remain interested in protecting finance capital from its challengers.

In 2007 Bannon helped found the avowedly fascist and extremely racist online outlet Breitbart, whose open support for white supremacy didn’t exactly challenge the foundations of the American political system so much as it correctly identified them. And it is for this reason that figures like Trump and Bannon are vocally condemned by their more “liberal” fellow members of the ruling class – because they “say the quiet part out loud.”

It is also fairly common to see politically naïve people claiming that figures like Steve Bannon represent the polar opposite of figures like John Bolton. Whereas Bolton represents Cold War-esque, trigger-happy, neoconservative fanaticism, Bannon is said to represent the “isolationist” conservative tradition that is less enthusiastic about foreign entanglements, and even imperialism itself. Once again, however, a nuanced look at the situation shows that these two “wings” of Trumpism, while genuinely different on a few issues, are far closer than many people think.

For one thing, it was Steve Bannon who encouraged Trump to hire John Bolton in the first place. According to Michael Wolff’s book Fire and Fury, in 2015 “Bannon said he’d tried to push John Bolton, the famously hawkish diplomat, for the job as National Security Advisor.” Indeed, Bannon had long been fascinated with the neoconservative icon, going so far as to routinely feature Bolton as a guest on his Breitbart radio program. This is not as surprising as it may first appear. While on a few issues Bannon had been less interventionist than Bolton (Bannon was apparently wary of confronting North Korea, a country that Bolton had publicly advocated pre-emptively bombing), they were largely in agreement on other issues. His known antisemitism notwithstanding, Bannon is a major supporter of Israel, boasting in a speech to the Zionist Organization of America that he was “proud to be a Christian Zionist.” This makes perfect sense: fascist forces tend to support one another, so a white supremacist like Bannon naturally sympathizes with a Jewish supremacist ethnostate like Israel. Furthermore, Bannon is also a lunatic anti-China hawk. According to Fire and Fury again, Bannon thinks that “China is where Nazi Germany was in 1929 to 1930,” which (aside from being a historically nonsensical comparison) ominously implies that the United States will have to confront it militarily at some point. All of this is perfectly compatible with Boltonian neoconservatism, and hardly qualifies as “anti-establishment.”

But it is on the issue of Iran where Bannon and Bolton converged the most. In part due to his Christian Zionism, Bannon is a militant Iran hawk, something that puts him in good company with Bolton, who has publicly advocated bombing Iran (there are very few places Bolton has not suggested the U.S. murder civilians in) as well as carrying out regime change there. Slate noted early in Trump’s first term that Bannon and Bolton were “allies” on the issue, and Vox reported that while he was still working from the White House, Bannon asked Bolton to draw up a detailed plan for leaving the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA, aka “the Iran nuclear deal”) – a top priority for Trump, Bannon, and Bolton alike. Bolton devised just such a plan, but was unable get it to Bannon, since by that point he’d been fired. Upon Bannon’s firing, Bolton put out a very nice statement on Twitter, congratulating Bannon for his accomplishments and wishing him the best of luck. Soon after, Trump hired Bolton, who was then able to implement his withdrawal plan, thereby needlessly ratcheting up tensions between the U.S. and Iran even further.

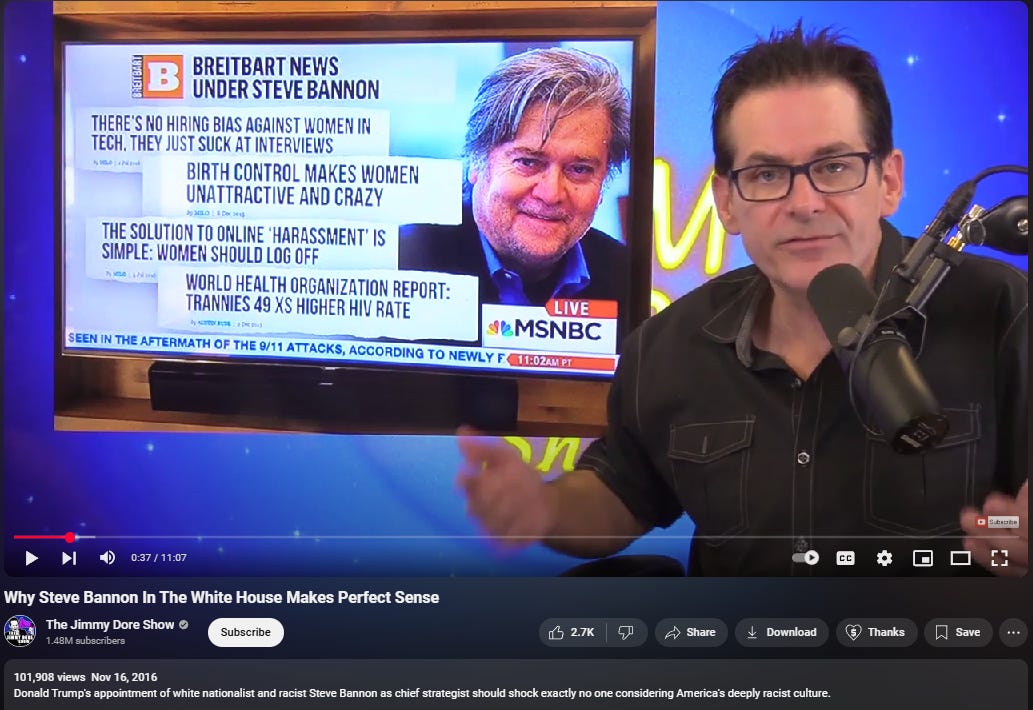

Ostensibly “anti-establishment” MAGA figures like Bannon are in reality just particularly noxious representatives of it. This is important to understand, because if you follow online discourse (which you should only do in moderation), you will see more than a few charlatans promoting such figures as viable alternatives to the political establishment. For example, the prominent YouTuber and former Young Turks contributor Jimmy Dore features Bannon as a guest on his show.

Prior to this, Dore had been flattering Bannon by claiming that “the establishment” was ostensibly “terrified” of him, and that “Among the prominent Trump supporters, perhaps no one reflects a true populist stance more than Steve Bannon.”

This is an interesting development for Dore, who not long ago was considered quite left-wing. Indeed, during the first Trump term, like most on the left Dore recognized Bannon for the vile racist that he is.

But ever since COVID, Dore has been gravitating further and further to the fringe right, taking much of his audience along with him. Indeed, since 2020, he has promoted risible ideas about vaccines, fully embraced climate change denial, platformed Daily Wire creep Matt Walsh, and on the whole has cultivated the impression that Trump is working for average (implicitly white) Americans. One of the last remaining traces of Dore’s political leftism has been his consistent opposition to U.S. militarism. Yet that stance is difficult to square with his cozying up to someone like Bannon, who, given his support for Israel, hawkishness toward Iran, and fearmongering about China, can fairly be described as a warmonger. One wonders if this isn’t the latest step in Dore’s ongoing transformation.

So what are the lessons here?

For one thing, there is no equivalence between the “populist left” and “populist right.” They are not equally worthy approaches to politics. In fact, the phrase “populist right” is a giant self-contradiction, since the term “populist” originated as the name of an avowedly left-wing movement that posed a serious threat to the two-party system in the late 19th century. The history of this movement is reviewed by Thomas Frank in The People, No: A Brief History of Anti-Populism. Frank highlights that the original Populists were pro-labor, anti-Gold Standard, lovers of mass education, multiracial, pro-immigration, and the only political party of their time to put women in positions of leadership. Indeed, this is why Martin Luther King Jr., just after wrapping up the famous March from Selma, Alabama, publicly praised the Populist Party, and lamented the ways in which the rich employed the classic tactic of sowing racism in order to crush them:

Toward the end of the Reconstruction era, something very significant happened. That is what was known as the Populist Movement. The leaders of this movement began awakening the poor white masses and the former Negro slaves to the fact that they were being fleeced by the emerging Bourbon interests. Not only that, but they began uniting the Negro and white masses into a voting bloc that threatened to drive the Bourbon interests from the command posts of political power in the South.

To meet this threat, the southern aristocracy began immediately to engineer this development of a segregated society. I want you to follow me through here because this is very important to see the roots of racism and the denial of the right to vote. Through their control of mass media, they revised the doctrine of white supremacy. They saturated the thinking of the poor white masses with it, thus clouding their minds to the real issue involved in the Populist Movement. They then directed the placement on the books of the South of laws that made it a crime for Negroes and whites to come together as equals at any level. And that did it. That crippled and eventually destroyed the Populist Movement of the nineteenth century.

The other lesson is that, whatever contrarian influencers would have you believe, Donald Trump is very much a major threat to important values and institutions, if not always in the exact same ways that mainstream liberals claim he is. The deeply pernicious idea that Trump, or Trumpism, or MAGA, are somehow antiwar or antiestablishment, needs to be put to death, and quickly. The actions of the second Trump administration thus far should have made this very obvious by now. Those actions are occurring at a dizzying pace (indeed that is the point, to disorient people), and cannot be sufficiently discussed here. Suffice it to say that the appointment of figures like Pete Hegseth, Marco Rubio, Elise Stefanik, and Mike Huckabee (all of whom are neoconservatives, Christian Zionists, Christian nationalists, or some combination of these) should remove any remaining doubts about Trump’s relationship toward “the establishment.” But in case any doubt remained, Trump’s calls for carrying out a second Nakba by ethnically cleansing Gaza should do the trick. Such calls, along with the rest of the Trump agenda, must be resolutely opposed by every thinking American.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author, expressed in an unofficial capacity, and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Navy, Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government.

We should also acknowledge that Trump did not exclusively campaign on foreign policy restraint: he was always extremely hawkish on Iran, as well as cartoonishly pro-Israel.